Church Girls Anonymous

Nothing says "doomed by the narrative" like a girl who was raised religious.

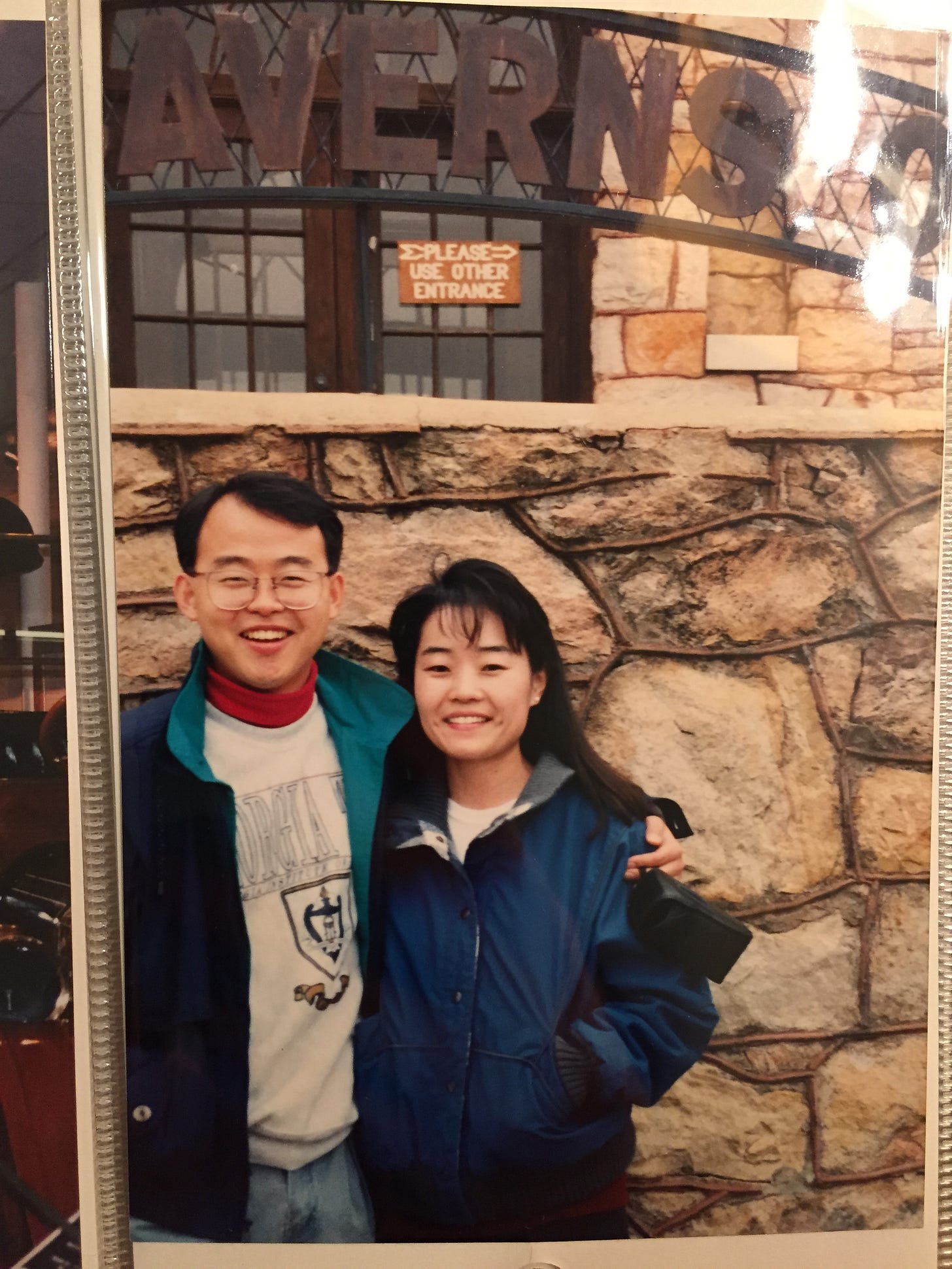

If it weren’t for church, I wouldn’t even exist. Hinge wishes it had half the success rate of the hallowed Church Singles Group™, where my parents met about 30 years ago. My dad got so nervous on their first date that a piece of food he was chewing somehow found its way out of his mouth and onto my mom’s face, but what’s a little ick like that compared to the thrill of your meet-cute taking place in the house of God? Everything that followed – a honeymoon in Hawaii, two daughters, shinguards and cleats left in a smelly pile by the garage door, summer trips to Busch Gardens and Water Country USA, sticky rosin fingerprints on the bannister – wouldn’t have been possible without church. It’s my origin story, for better and for worse. At various points in my life I’ve fashioned myself into a devout believer, a sneering skeptic, and an indifferent outsider to the institution, but the truth is that it’s always been part of my DNA.

My inherited faith is an ill-fitting garment. It puckers and sags in all the wrong places, and whenever I try it on anew I wonder how I managed to delude myself into thinking it might be different this time. Spring cleanings come and go, and still it hangs in the back of my closet gathering dust. It compels and repulses me in the same breath; I wish I could bring myself to throw it out for good. This feeling of being caught in church’s gravitational pull is central to Deesha Philyaw’s debut short story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which she dedicates to “everyone trying to get free.” A handful of Big Ideas tie all nine vignettes together – religious patriarchy, compulsory heterosexuality, and mothers who love the church more than their own daughters – but Philyaw is not a preacher (and praise God for that), so there are no cloying moral fables to be found here. Her heroines are varied and complex, and their relationships to other people, not religion, are the focal point of the stories. As her characters fight and fuck and feed one another, Philyaw illustrates in piercing, richly drawn detail how the black church has shaped and stymied their desires, trained them to hide and lie and serve, and left them with an aching loneliness that no amount of prayer can cure.

Take Olivia, the narrator of “Peach Cobbler.” Raised on a diet of ready-made TV dinners, she yearns for one homemade dish in particular: peach cobbler. Every Monday, she catalogs her mother’s painstaking process of making it from scratch and then watches her forbidden fruit vanish, forkful by forkful, into the greedy stomach of the married pastor from their church. Cobbler teaches Olivia two things that come to define her young life: how to keep secrets, like her mother’s affair, and how to be hungry. What she craves above all is her mother’s attention and tenderness, but they’re finite resources reserved entirely for the pastor and the peaches. Olivia confesses, “I wanted to be those peaches. I longed to be handled by caring hands.” It might not be singing hymns in a church pew on Sunday morning, but her mother’s ritual of washing and slicing fresh peaches at the kitchen sink has the same rhythms of worship. “She always said Sunday was her Saturday and Monday was her Sunday,” Olivia tells us. And what do church ladies do on Sabbath? Present an offering to God, of course. Instead of a $10 bill placed into a collection plate, her mother offers an entire pan of “the best cobbler in the world” for the pastor’s sole consumption. It’s no wonder Olivia believed that “God and Reverend Troy Neely were one and the same” until she was eight. God gets to eat cobbler at the kitchen table with utensils in broad daylight; if mere mortals like her want a taste, they have to sneak into the kitchen under the cover of darkness and blindly dig handfuls of it out of the trash.

Olivia’s hunger is not an accident. Her mother is its very architect, telling the pastor that it’s better for Olivia to never have good things than to get “a taste of that sweetness” because then “she’s going to want it so bad, she’ll grow up and settle for crumbs of it.” But depriving Olivia of love only makes her appetite for it grow, and soon she’s looking for softness in places and people who have only stale crumbs to offer. Like mother, like daughter. The unnamed narrator in a different story, “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands,” paints an ominous picture of Olivia’s potential future. The cobbler-making student has become the master, now so adept at being The Other Woman that she’s developed a handy guide for the feckless men that enter her orbit, like her own personalized edition of Cheating For Dummies. The narrator’s contempt for her partners in infidelity oozes from every mocking word (“I am not [your therapist]. … This is one of the safeguards that keeps feelings at bay, and more importantly, it keeps me from resenting you the way your wife does”), but she herself isn’t spared from reproach: “I grew up watching my mother eating the crumbs and leftovers from another woman’s table. I swore I never would. But here I am grubbing, licking the edges.” Whether or not Philyaw intends this narrator to actually be Olivia from “Peach Cobbler” once she’s all grown up, it’s an effective callback to illustrate the all-too-common cycle of women watching their mothers settle for crumbs and resigning themselves to the same fate.

Mommy issues take on a slightly different shape in “Snowfall,” which tells the story of Arletha and Rhonda – two women whose love for each other means they’re in exile from the South, their childhood churches, and their mothers. Rhonda says that home will bloom wherever Arletha is planted, but Arletha can’t quite kick the creeping dread that she has no home at all, not now that she’s cut off from “the laughter and embrace of our mothers and grandmothers and aunties, kin and not kin.” She mourns the warmth of this community even as she picks at the scabs left by her mother’s refusal to acknowledge her sexuality as anything other than a defect to fix through prayer. “As I walked out her front door for the last time eight months ago,” Arletha says, “she hurled the words at my back: ‘Running off from here with some girl you met on the internet. Who raised you?’” Knowing your mother’s love is conditional unfortunately doesn’t stop you from wanting to be bundled in its suffocating embrace. Distance and time may help dull the sharpness of the pain, but those bruises linger for a long time. When something incredible happens, or something terrible, funny, confusing, maddening – your brain, the traitor, reaches for her with childlike instinct. “How could my mother’s world just keep right on spinning without me in it?” Arletha wonders to herself. “Maybe it hadn’t. Maybe she was lying in bed thinking about me too, worrying. Maybe.”

For some church ladies, sapphic passion isn’t nearly as angst-ridden. The titular character of “Jael” is interested in one thing and one thing only: Sister Sadie, the pastor’s wife. Her diary is filled with daydreams that are by turns adorable and horny, all focused on “Sweet Sadie” and “her sexy body and her secret past.” 14-year-old Jael feels no shame about her crush, no matter how fervently her snooping grandmother prays for her “reprobate mind” to be cleansed. Rhonda and Olivia would do almost anything for maternal approval, but Jael seems unconcerned with what her grandmother (who raised her nearly from birth) thinks of her. The direct contrast between Jael fantasizing about Sadie wearing a white bikini while riding a motorcycle and Jael’s grandmother frantically citing scripture to counteract the “sinful” things she’s reading is so funny, not least because my mom regularly texts me Bible verses without any context, as though she’s locked in an unspoken battle for my soul and the only way to save me from the bisexual thoughts is to find the right Biblical passage to drive the devil out.

Jael is distracted from her life’s true purpose (thinking about what Sadie looks like under her demure church suits) by a 35-year-old creep who keeps hounding her and her 15-year-old friend, Kachelle, to come to his house or let him take them to the beach, just the three of them. Jael sees right through the predator, but Kachelle falls for it hook, line, and sinker, and won’t hear a word against him. There’s nothing left for an adolescent lesbian to do but go Old Testament on his ass. And I mean that literally – Philyaw’s Jael is a tongue-in-cheek reinterpretation of a little-known Biblical heroine who murders the commander of the Canaanite army by driving a tent peg through his skull. The church elders must really hate to see a girlboss winning, because in all my years of small groups, summer camps, and Bible study sessions, I had never even heard of Jael. Her story comes in the Book of Judges, which is basically about God giving select people the ability to go Super Saiyan on Israel’s enemies. In other words, Jael’s ruthless act of violence against a powerful man is extolled and blessed by the highest power there is. She acts as judge, jury, and executioner, and God is just like, okay … work. No more gatekeeping Jael from church girls!

Of all the things about Jael that disturb her grandmother, the disparity between her “innocent” external appearance and her salacious inner life seems to be the most offensive: “She look sweet in the face. Folks think she just quiet. But in her heart, her spirit, her mind … That ain’t of God.” Once the veil has been lifted on the secrets of church ladies, you can’t unlearn their truths. It’s like closing your eyes after a bright camera flash or fireworks have gone off in front of you – the image lingers. Philyaw’s collection is that bright flash, allowing you to look at the people seated around you in church and see double: the face that they present to the rest of the congregation, and the afterimage of everything they pretend not to be.

P.S. I know my last post was one long complaint about how screen adaptations are the lowest common denominator of content, but Tessa Thompson is producing an adaptation of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies for HBO Max and I absolutely will be tuning in. I’m part of the problem, I know, but this is prime Iris bait.

Other things I’ve watched/read/listened to recently:

Polite Society: From the mind that brought you We Are Lady Parts comes a movie about how younger sisters are right even when we’re being super annoying about it, why boy moms are the real villains, and the life-saving potential of a teenage girl’s hyper-fixation. Writer-director Nida Manzoor just gets it – the intensity and silliness of female friendships, how weird and imaginative and funny it can be inside a young woman’s brain, and the cocktail of guilt, stubbornness, and doubt that comes with being an Asian woman whose creative passion doesn’t align with cultural expectations for people who look like us.

“Learning and Not Learning Abortion” by Laura Kolbe for n+1: I tend to think of abortion access in terms of the patient experience, but things aren’t looking so hot on the healthcare providers’ side of things either. This history of “systemic incompetence” in abortion training and practice is both fascinating and depressingly unsurprising – like, of course the AMA boy’s club spearheaded the U.S. movement to criminalize abortion in the mid-1800s because they wanted to discredit midwives and put them out of business. Of course the University of Arizona stopped teaching and providing abortions in exchange for a new football stadium. We know that those in power have no hang-ups about endangering the health and safety of half of the world’s population as long as they can profit from it, but to see it all laid out like this – what a thorough fucking job they’ve done.

“The aim is not just to make abortions unavailable at publicly funded hospitals and medical establishments. It’s also to create fewer and fewer abortion-competent American physicians each year—a gap in knowledge that follows physicians for the rest of their clinical lives.”

“Everyone Who Knows What Elizabeth Holmes Did Wrong, Step Forward (Not So Fast, The New York Times)” by Albert Burneko for Defector: New York legacy media outlets love to publish puff pieces on the worst people imaginable, neglect to mention why people are actually mad at them, and then act like the whole issue is just too complex to take a stance on. It’s actually very simple: Elizabeth Holmes lied about what her company’s technology could do over and over and over again, she knew she was going to seriously hurt people (or worse), and she didn’t care as long as she was able to live out her Steve Jobs fantasy. The end.

“So it's kind of incredible to read a reporter wringing their hands—even if only as a theatrical performance of Grappling With The Unknowability Of Others—over the question of whether or not you can really trust the weird-voice lady who says she's all better now. I don't care!”

Half of my arm got sunburnt while I was eating lunch outside this week, which means “Say It” by Maggie Rogers season is nearly upon us!!! A happy almost-summer to all.