It’s an unfortunate fact of life that sometimes people who are really annoying also happen to be correct – and when it comes to Bodies Bodies Bodies, Lena Wilson (a film critic for the New York Times and notable member of the annoying community) mostly hit the nail on the head. Putting aside the line in her biting review that Amandla Stenberg, one of the movie’s stars, specifically took issue with (“… it doubles as a 95-minute advertisement for cleavage and Charli XCX’s latest single”), there isn’t much to argue with. Is Bodies Bodies Bodies, as Wilson writes, a whole lot of style without substance and half-baked in its attempt at satire? Yes. Did I have fun watching it? Also yes. At the end of the day, when a movie produces as much gossip and drama as this one has in the weeks following its release, it’s a win for all of us:

But let’s not lose sight of what really matters here: Bodies Bodies Bodies is yet another entry in the Rachel Sennott scene-stealing canon. As Alice, an insecure podcaster who finds all sides of an argument equally convincing and whose vocabulary is 90% therapy-speak buzzwords, Sennott is the funniest part of director Halina Reijn’s slasher and embodies the most coherent caricature of The Youths. We all know an Alice – the girl who would invite a weird older guy she met on a dating app a few days ago to a friends-only getaway based purely off of vibes (“He’s a libra moon, that says a lot!”). She’ll congratulate you on your newfound sobriety while parading a veritable buffet of drugs and alcohol right under your nose and wears her self-diagnosis of body dysmorphia like a badge of honor. She’s never, not even once, said anything profound on her podcast.

Still, I found myself wishing she had gotten more to do – maybe because I recently watched her put on a 77-minute masterclass in psychological torture in Tahara, a 2020 coming-of-age movie about two teens trying to get through the funeral of a fellow Hebrew school classmate who died by suicide. Alternatively, Tahara is the story of getting queerbaited by your best friend (Sennott), who you know deep down is terrible – and most likely straight – but who you can’t help being obsessed with anyway.

Of all the things Tahara gets right about teen girldom, the sanctity of a bathroom break – and who you choose to take it with – is paramount. Saying you need to go to the bathroom while eyeing your best friend meaningfully is an act of intimacy. It doesn’t matter if all you end up doing in there is watch her pop a pimple and listen to her complain about a boy who isn’t paying her enough attention – the invitation itself is the point. And who knows? Maybe one day something of real consequence will take place among the chilly, echoing tiles; something like Hannah (Sennott) asking Carrie (DeFreece) to confirm that she’s a good kisser.

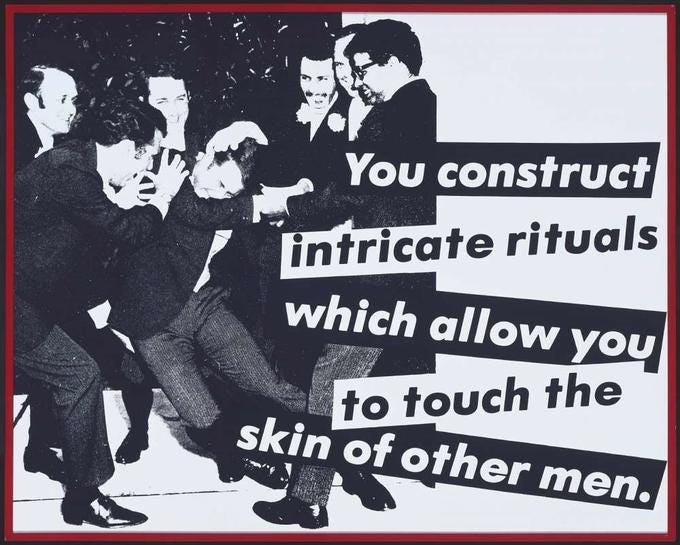

When Barbara Kruger observed in 1981 that men construct intricate rituals which allow them to touch the skin of other men, she couldn’t have predicted that her words would one day be applied to Tom and Greg from Succession, hockey players, and Formula 1 drivers (the top results from the #intricate_rituals tag on Tumblr). But what about the intricate rituals that teen girls construct to touch the lips of other girls? Deciding to crush on a boy is only 50% about the thirst object himself, at most. The other, more exciting half, is taken up by talking about him to other girls; thinking about girls who might also like him and comparing yourself to them; and playacting your potential courtship by casting girls in your love interest’s role.

In Tahara, Hannah only speaks directly to her crush, Tristan Leibotwitz (Daniel Taveras), in two or three scenes. Her fixation on him is expressed almost entirely through conversations with her best friend, Carrie. So the fact that Hannah’s infatuation feels so all-consuming, like her life force is directly linked to how much interest Tristan shows in her, is a testament to the power of the aforementioned intricate rituals. She asks Carrie to kiss her in the bathroom because she wants to make sure she knows what she’s doing before she lays one on Tristan, who’s completely indifferent to Hannah and has a sweetly fumbling interest in Carrie, who in turn just wants to kiss Hannah again. The only thing that can distract Hannah from acting like a horny lion stalking her unsuspecting prey is Carrie taking a one-on-one bathroom break with someone else – a betrayal of the highest order.

More suffocating than the repressive funeral mood and Hebrew school-mandated discussions about grief and mental health is Hannah’s insistence that nothing needs to change between her and Carrie after their kiss. What’s a little mouth-to-mouth action between two gal pals? It was for the greater good, for science, for Hannah’s reputation as a budding vixen! And yet, at the first indication that Carrie no longer prioritizes Hannah as her closest friend, Hannah panics. Meteorologists can only dream of being as sensitive to the slightest shifts in the social climate as teenage girls are. Hannah doesn’t need a complicated mathematical equation to know that Carrie upending the bathroom break protocol is an unambiguous sign of impending natural disaster.

Rachel Sennott leans into Hannah’s blithe self-absorption without flinching. While Alice in Bodies Bodies Bodies feels like a girl I know and want to stay far away from, I recognize in Hannah parts of my adolescent self that I’d rather forget: the way she constantly tests the limits of the people closest to her for no reason other than because she can; her manipulative tendencies; her cliquishness; and the inexplicable mix of self-consciousness and ego that makes her seem vulnerable one minute and irredeemable the next. She’s all soft underbelly masquerading as impenetrable armor, just waiting to be sliced through in one stroke.

Madeline Grey DeFreece’s Carrie, on the other hand, plays the audience surrogate – even as we feel her impatience with Hannah’s performance of a crush as if it’s our own, we, too, hold out hope that this time it’ll be different. This time, Hannah will acknowledge and treat Carrie’s feelings with respect. This time, Hannah will reciprocate them unambiguously. Carrie becomes disillusioned with this unfounded optimism over the course of the movie, but she never loses the decency and kindness at her core. The Hebrew meaning of “Tahara,” according to Google, is a cleansing of the body. When Carrie drives away from the funeral (and from Hannah) at the end of the movie, we get the sense that the deceased wasn’t the only one who was purged of something.

If I could commission a Tahara fancam, it would be set to Lucy Dacus’s “Kissing Lessons” – the anthem for girls who obsessed over boys as a way to obsess over their best friends. Friendship, romance, desire, jealousy, affection, frustration, intimacy, and the mortifying ordeal of being known – they’re all tied up in Hannah and Carrie’s kissing lessons.

I asked her how to win my man

And she said, "I know just the thing"

Gave me lipgloss and a hair toss

And, after school, a lesson in kissing

She called me by the name of her crush

I couldn't decide if she was Cole or Justin

I think I called her baby or darling

Most the time

We'd take turns being seduced

Imagining the day it would come into use